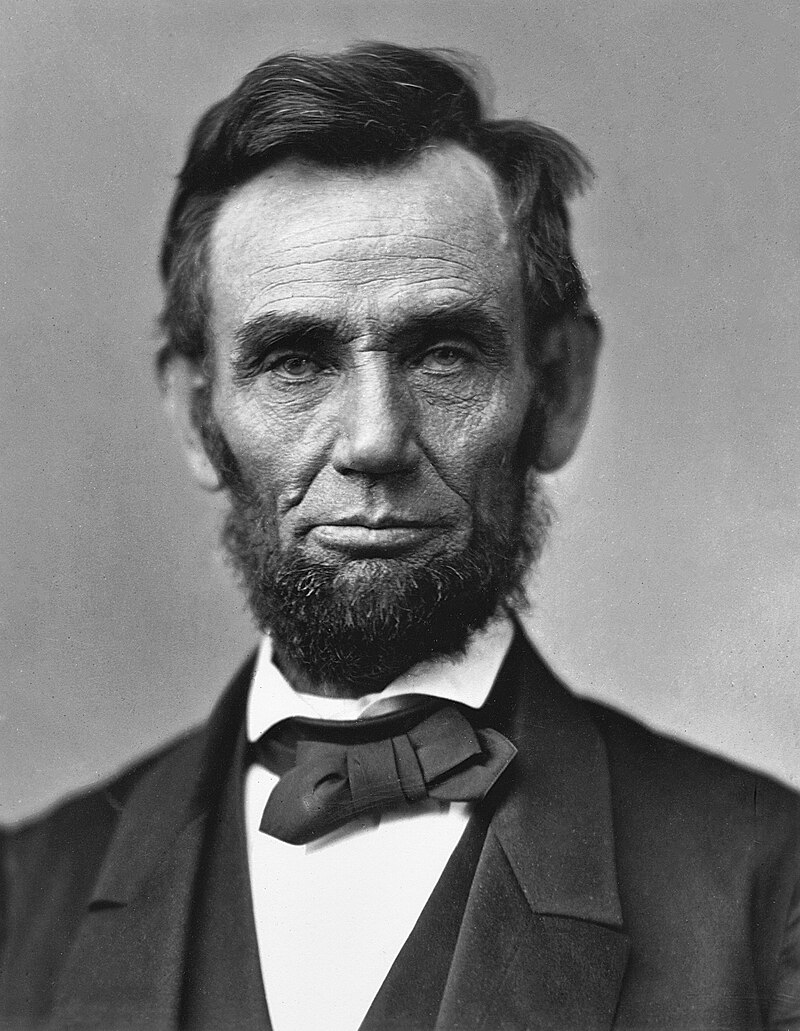

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) was the 16th President of the United States, serving from 1861 to 1865. Widely regarded as one of the greatest presidents in American history, he is renowned for his leadership during the American Civil War, preserving the Union, and issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, a pivotal step in ending slavery. Lincoln’s eloquence, exemplified in speeches like the Gettysburg Address, and his commitment to equality have solidified his lasting impact on the nation.

Early Life and Education

Abraham Lincoln’s early life and education laid the foundation for a remarkable journey from a log cabin in Kentucky to the presidency of the United States. Born on February 12, 1809, in Hardin County (now LaRue County), Kentucky, Lincoln was the second child of Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks Lincoln. The family’s economic circumstances were modest, and life on the frontier presented numerous challenges.

The Lincoln family’s financial struggles led them to move to Indiana in 1816, where young Abraham experienced the hardships of pioneer life. Tragically, in 1818, when Lincoln was just nine years old, his mother, Nancy, succumbed to milk sickness, a common ailment in the region. Her death had a profound impact on Lincoln, leaving him with a sense of loss that would resonate throughout his life.

Thomas Lincoln, Abraham’s father, remarried the following year to Sarah Bush Johnston, a widow with three children of her own. Sarah played a pivotal role in young Abraham’s life, fostering his love for learning and providing a stabilizing influence. Despite the family’s limited resources, she encouraged his education, recognizing his intellectual potential.

Lincoln’s formal education was minimal, consisting of brief periods in frontier schools where he learned the basics of reading, writing, and arithmetic. His education was irregular, as he often had to work to help support the family. Nonetheless, Lincoln displayed a keen interest in learning and exhibited a voracious appetite for reading.

In 1830, the Lincoln family, seeking improved economic prospects, moved once again, this time to Macon County, Illinois. Abraham, now in his twenties, began to strike out on his own. His years in Illinois were marked by various jobs, including working as a rail-splitter, store clerk, and postmaster. These experiences not only contributed to his work ethic but also exposed him to the realities of life on the expanding frontier.

One of Lincoln’s pivotal experiences during this period was serving in the Illinois militia during the Black Hawk War of 1832. Though the conflict was brief and inconclusive, it provided Lincoln with some exposure to military life and leadership, foreshadowing the challenges he would face decades later as President during the Civil War.

Despite the economic and personal challenges, Lincoln’s determination to educate himself remained steadfast. He utilized any opportunity to borrow books, often walking long distances to borrow volumes from neighbors. His reading covered a wide range of subjects, including law, literature, and politics. Books such as the Bible, Aesop’s Fables, and Shakespeare’s works left a lasting imprint on his rhetorical style and moral outlook.

In 1832, Lincoln made his first foray into politics, running for a seat in the Illinois State Legislature as a member of the Whig Party. Although he did not win, this campaign marked the beginning of his political career. Two years later, in 1834, he won a seat in the legislature, serving four consecutive terms. During this time, he continued to study law on his own, laying the groundwork for his future legal career.

Lincoln’s passion for the law led him to seek admission to the bar. In 1836, he achieved this milestone and commenced his legal practice in Springfield, Illinois. The following year, he was elected to the Illinois State Legislature and began building a reputation as a capable and honest politician. His legal career flourished, and he gained a reputation for fairness and integrity in his dealings.

In 1842, Lincoln married Mary Todd, a woman from a prominent Kentucky family. The couple would go on to have four sons: Robert, Edward, William, and Thomas. However, tragedy struck the Lincoln family with the death of their second son, Edward, at a young age.

Abraham Lincoln’s early life was marked by perseverance in the face of adversity, a commitment to self-improvement, and a growing presence in the world of Illinois politics. His experiences on the frontier, combined with a thirst for knowledge and an innate sense of justice, shaped the qualities that would later define his presidency. As he navigated the challenges of the rapidly changing nation, these formative years provided the crucible in which Lincoln’s character and leadership qualities were forged.

Political Career

Abraham Lincoln’s political career was a journey that saw him rise from the Illinois State Legislature to become the 16th President of the United States during one of the nation’s most challenging periods – the Civil War. His political ascent was marked by a commitment to preserving the Union and a fervent opposition to the expansion of slavery.

Lincoln’s early political career gained momentum in the 1830s when he served in the Illinois State Legislature as a member of the Whig Party. During this time, he demonstrated an ability to navigate the complexities of state politics while honing his skills as a persuasive speaker. His reputation as an honest and hardworking legislator began to take shape, setting the stage for his future endeavors.

In 1836, Lincoln received his license to practice law and embarked on a legal career in Springfield, Illinois. His involvement in politics continued, and he gained election to the Illinois State Legislature in 1834, 1836, 1838, and 1840. Throughout these years, he developed a keen interest in infrastructure development, advocating for improvements such as roads and canals that would benefit the growing state.

Lincoln’s focus on law and politics intertwined, as he leveraged his legal acumen to navigate the political landscape. In 1846, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives as a member of the Whig Party. Lincoln’s single term in Congress from 1847 to 1849 coincided with the tumultuous debate over the Mexican-American War. While he initially supported the war, he later questioned its origin and demanded that President James K. Polk specify the exact location where hostilities began.

Upon returning to Springfield after his congressional term, Lincoln resumed his legal practice, earning a reputation as a skilled and ethical lawyer. His political ambitions, however, were undeterred. As the nation grappled with the divisive issue of slavery, the political landscape underwent a significant transformation. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 had temporarily maintained a balance between free and slave states, but the acquisition of new territories reignited the debate.

The passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, which allowed territories to decide on the issue of slavery through popular sovereignty, intensified tensions. This event prompted Lincoln to reenter politics, and he aligned himself with the newly formed Republican Party, an anti-slavery political force. In 1856, he campaigned for the Republican candidate John C. Frémont, and by 1858, he emerged as a prominent figure within the party.

The Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858 marked a critical point in Lincoln’s political career. His opponent, Senator Stephen A. Douglas, advocated for popular sovereignty on the issue of slavery. Lincoln, however, argued that the nation could not endure permanently half slave and half free. The debates were widely covered in the press and elevated Lincoln’s national profile, even though he lost the Senate race to Douglas.

The following year, in 1859, Lincoln delivered a speech in New York City at the Cooper Union, further solidifying his reputation as a serious political figure. The speech emphasized his opposition to the expansion of slavery and resonated with anti-slavery sentiments in the North.

The Republican National Convention of 1860 saw Lincoln emerge as the party’s presidential candidate. His nomination was a reflection of the Republican Party’s commitment to preventing the spread of slavery into new territories. The Democratic Party, split along regional lines, nominated multiple candidates, leading to a divided electorate.

In the 1860 presidential election, Lincoln won a decisive victory in the Electoral College, securing 180 electoral votes. His victory, however, did not sit well with Southern states that feared Republican policies would threaten their institution of slavery. The secession crisis unfolded, leading to the formation of the Confederate States of America and the outbreak of the Civil War.

Upon his inauguration on March 4, 1861, Lincoln faced the daunting task of preserving the Union. The Southern states’ secession presented a direct challenge to the authority of the federal government. Lincoln, committed to maintaining the integrity of the nation, declared secession illegal and embarked on a course to reunite the divided states.

Throughout the Civil War, Lincoln faced intense political pressures and military challenges. He made key strategic decisions, including the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, which declared all slaves in Confederate-held territory to be free. While this did not immediately free all slaves, it changed the moral tone of the war and aligned Union forces with the cause of ending slavery.

In 1864, Lincoln faced a contentious reelection campaign against Democratic candidate George McClellan. Despite setbacks and public discontent over the prolonged war, Lincoln prevailed. His leadership during the war and his commitment to principles such as the preservation of the Union and the abolition of slavery cemented his legacy as one of America’s greatest presidents.

Tragically, Lincoln’s life was cut short by an assassin’s bullet on April 14, 1865, just days after the war’s conclusion. His assassination marked a somber end to a political career that had navigated the nation through its darkest hour.

Abraham Lincoln’s political career was marked by a steadfast commitment to principles, astute leadership during a tumultuous period, and a dedication to preserving the Union. His legacy endures as a symbol of unity, freedom, and the enduring pursuit of justice in the face of adversity.

Presidency

Abraham Lincoln’s presidency, from 1861 to 1865, is etched in history as a defining chapter in the United States. Leading the nation through the Civil War, Lincoln faced unprecedented challenges, demonstrating leadership, resolve, and a commitment to principles that would shape the future of the country.

Lincoln assumed office on March 4, 1861, at a time when the nation was on the brink of division. Southern states had already seceded, forming the Confederate States of America. The new president inherited a deeply divided nation and the monumental task of preserving the Union. In his inaugural address, Lincoln appealed for unity, stating, “We are not enemies but friends. We must not be enemies.”

As the Confederacy seized federal forts and arsenals, tensions escalated, and on April 12, 1861, Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. This marked the beginning of the Civil War, a conflict that would test the resilience of the nation and the leadership of its president.

Lincoln’s approach to the war was rooted in his dedication to preserving the Union. Initially, he framed the conflict as a rebellion that needed to be suppressed, emphasizing the constitutional duty of the federal government to maintain its authority. The war’s early stages were marked by a series of Union defeats, and the president faced criticism for what some perceived as indecision.

However, Lincoln’s leadership style evolved as the war progressed. He began to grasp the magnitude of the conflict and the need for a more robust and strategic approach. In 1862, he introduced the Emancipation Proclamation, a groundbreaking executive order that declared all slaves in Confederate-held territory to be free. While this did not immediately free the slaves, it changed the character of the war, making the abolition of slavery a central goal for the Union.

The Battle of Antietam in September 1862 provided a crucial turning point. Although it was one of the bloodiest battles of the war, it ended in a tactical draw. Nonetheless, it gave Lincoln the opportunity to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, signaling the Union’s commitment to ending slavery. The final proclamation was issued on January 1, 1863, and it added a moral imperative to the Union cause, framing the war as a struggle for freedom.

Lincoln faced criticism and opposition, even within his own party, over issues such as the draft and the suspension of habeas corpus. However, he maintained a firm grip on the direction of the war. The selection of Ulysses S. Grant as the commanding general of the Union Army in 1864 proved pivotal. Grant’s aggressive tactics and commitment to total war brought about decisive victories for the Union, albeit at a heavy cost.

The election of 1864 was a crucial moment in Lincoln’s presidency. Despite facing significant political challenges and discontent over the prolonged war, Lincoln secured his reelection. His victory was a testament to the public’s belief in his leadership and the Union cause.

As the war neared its conclusion in early 1865, Lincoln focused on the task of reconstructing the nation. His vision for reconstruction emphasized a lenient approach toward the Southern states, seeking to bring them back into the Union with minimal retribution. Lincoln’s second inaugural address in March 1865 reflected his commitment to healing the nation’s wounds, famously stating, “With malice toward none, with charity for all.”

Tragically, Lincoln’s presidency was cut short by an assassin’s bullet. On the evening of April 14, 1865, while attending a play at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., John Wilkes Booth shot the president. Lincoln succumbed to his injuries the following day, becoming the first U.S. president to be assassinated.

Lincoln’s presidency left an indelible mark on American history. His leadership during the Civil War, commitment to the preservation of the Union, and advocacy for the abolition of slavery have solidified his legacy as one of the nation’s greatest leaders. The Emancipation Proclamation and the Gettysburg Address, delivered in November 1863, are enduring symbols of his dedication to freedom and equality.

The Gettysburg Address, delivered on the battlefield where thousands had perished, succinctly encapsulated the principles for which the Union fought. Lincoln’s words, “that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth,” resonated not only with the immediate audience but with generations to come.

Lincoln’s presidency demonstrated that the nation could weather the storms of internal strife and emerge with a renewed commitment to its founding principles. Despite the immense challenges he faced, Lincoln’s leadership during a pivotal period in American history secured his place as a symbol of unity, perseverance, and the enduring pursuit of a more perfect union.

Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, issued by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, stands as one of the most significant milestones in American history. This executive order forever altered the course of the Civil War and transformed the conflict from a struggle to preserve the Union into a moral crusade against slavery. The Emancipation Proclamation was a watershed moment that underscored the evolving nature of the Union’s goals and reshaped the trajectory of the nation.

At the onset of the Civil War in 1861, the primary objective for both the Union and the Confederacy was the restoration or secession of the Union, respectively. While the moral issue of slavery simmered beneath the surface, it wasn’t initially the central focus of the conflict. However, as the war unfolded and the Union faced setbacks on the battlefield, the need for a more profound moral purpose became apparent.

In the early years of the war, Lincoln faced the challenge of managing conflicting interests within the Union. Border states like Maryland, Kentucky, Missouri, and Delaware still permitted slavery, and Lincoln needed to maintain their support for the Union cause. Balancing these competing concerns was a delicate task, as a strong stance against slavery risked alienating crucial states.

The Emancipation Proclamation emerged as a strategic and moral response to the evolving nature of the war. Lincoln recognized that the Union needed a cause that resonated with its citizenry and the broader international community. Additionally, the Union sought to undermine the Confederacy’s economic and military infrastructure, much of which relied on the institution of slavery.

The preliminary Emancipation Proclamation was issued on September 22, 1862, after the Union victory at the Battle of Antietam. This battle, fought in Maryland, provided a critical turning point and an opportunity for Lincoln to make a bold move. The preliminary proclamation warned that if the Southern states did not return to the Union by January 1, 1863, all slaves in those states would be declared free.

On January 1, 1863, with no Confederate states having returned to the Union, Lincoln fulfilled his promise and issued the final Emancipation Proclamation. This executive order declared “that all persons held as slaves” within the Confederate states “are, and henceforward shall be free.” However, it explicitly exempted the border states and areas of the Confederacy under Union control.

The Emancipation Proclamation marked a significant shift in the Union’s goals. While it did not immediately free all slaves, it fundamentally changed the character and purpose of the war. The proclamation made the abolition of slavery a central objective of the Union, turning the conflict into a struggle for freedom and equality.

One of the crucial diplomatic implications of the Emancipation Proclamation was its impact on international perceptions. By aligning the Union cause with the abolition of slavery, Lincoln sought to gain support from European nations, particularly Great Britain and France, which had abolished slavery. This strategic move aimed to prevent these countries from recognizing the Confederacy and providing support.

While the Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery in and of itself, it had profound effects on the Union war effort. It gave a moral purpose to the conflict, energizing abolitionists and attracting African Americans to join the Union Army and Navy. Approximately 200,000 African Americans, both free and formerly enslaved, served in the Union military, contributing significantly to the Union’s victory.

Moreover, the proclamation paved the way for the eventual abolition of slavery through constitutional amendments. Lincoln recognized the need for permanent legal measures to eradicate slavery, and he supported the passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution. Ratified in December 1865, this amendment officially abolished slavery in the United States.

While the Emancipation Proclamation had limitations, including its geographical scope and its reliance on executive authority during wartime, its symbolic and practical impact cannot be overstated. It signaled a moral commitment to freedom, influenced the course of the war, and set the stage for the broader struggle for civil rights that would unfold in the post-war era.

The Emancipation Proclamation remains a testament to the complexities of leadership during times of crisis. Lincoln’s willingness to evolve and adapt to the changing nature of the war demonstrates the dynamic nature of his presidency. By issuing the proclamation, he not only transformed the Union’s war effort but also contributed to the broader arc of American history, laying the groundwork for a more just and inclusive society.

Gettysburg Address

Delivered on November 19, 1863, the Gettysburg Address by President Abraham Lincoln stands as one of the most iconic and revered speeches in American history. Given during a dedication ceremony for the Soldiers’ National Cemetery at the site of the Battle of Gettysburg, the address encapsulates the essence of American democracy, the sacrifice of the Civil War, and the enduring pursuit of a “new birth of freedom.”

The Battle of Gettysburg, fought from July 1 to 3, 1863, was a pivotal engagement in the Civil War. With staggering casualties on both sides, it marked a turning point in favor of the Union. The magnitude of the loss prompted the establishment of a national cemetery to honor the fallen soldiers, and Lincoln was invited to deliver a few appropriate remarks at its dedication.

Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, though brief, is a masterpiece of concise and impactful rhetoric. In just over two minutes, he addressed the fundamental principles of the nation, reflected on the sacrifices made on the battlefield, and articulated a vision for the future. The opening lines, “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal,” eloquently harked back to the founding of the United States and the ideals that underpinned its creation.

The central theme of the Gettysburg Address is encapsulated in Lincoln’s assertion that the nation is engaged in a great “civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.” Lincoln framed the conflict not merely as a struggle to preserve the Union but as a test of the very principles upon which the nation was founded – a test of whether a government “of the people, by the people, for the people” could endure.

The speech then shifted to a poignant acknowledgment of the sacrifices made by those who fought on the battlefield. Lincoln expressed that it was altogether fitting and proper to dedicate a portion of the nation’s consecrated ground as a final resting place for those who had given their lives. He emphasized that the living had a solemn duty to ensure “that these dead shall not have died in vain – that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom.”

The phrase “a new birth of freedom” encapsulates Lincoln’s vision for the nation’s future. He recognized that the war was not merely a struggle to preserve the Union but a moral reckoning with the institution of slavery. The Emancipation Proclamation, issued earlier in 1863, had declared slaves in Confederate-held territory to be free, aligning the Union’s cause with the broader fight for liberty and equality.

Lincoln’s emphasis on equality and the idea that the United States was a nation dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal was a radical departure from the prevailing racial attitudes of the time. In the context of the mid-19th century, with slavery still deeply entrenched in the South, Lincoln’s words were a bold declaration of the nation’s commitment to the principles of the Declaration of Independence.

The brevity and simplicity of the Gettysburg Address belie its profound impact. Lincoln’s eloquence and moral clarity resonated not only with those present at the dedication but with future generations. The address became a touchstone for the nation’s identity, reminding Americans of the enduring principles that bind them together.

The Gettysburg Address also contributed to a shift in the perception of the Civil War. It reframed the conflict as a struggle for a new birth of freedom and emphasized the transformative potential of the nation’s ordeal. Lincoln’s words resonated with a sense of national purpose and a commitment to building a more just and inclusive society.

While the Gettysburg Address was initially met with mixed reviews, its stature grew over time. Today, it is regarded as one of the greatest speeches in American history, studied for its rhetorical brilliance and its timeless articulation of democratic principles. Its brevity, combined with its profound message, makes it a masterpiece of concise communication, encapsulating the essence of the American experiment in a few hundred words.

As the United States faced the challenges of the Civil War, Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address provided a moral compass for the nation. It reminded Americans that their experiment in democracy was worth preserving, and that the sacrifices made on the battlefield were not in vain. The address endures as a testament to the enduring power of words to inspire and shape the course of a nation.

Personal Struggles

Abraham Lincoln’s life was marked by a series of personal struggles, from the hardships of his early years to the immense challenges he faced as President during the Civil War. These struggles not only shaped his character but also contributed to his resilience, empathy, and commitment to the principles of democracy.

Lincoln’s early life was one of poverty and frontier hardship. Born on February 12, 1809, in a log cabin in Hardin County, Kentucky (now LaRue County), he grew up in a family that faced constant economic challenges. His father, Thomas Lincoln, was a farmer, carpenter, and land surveyor, and the family moved frequently in search of better opportunities.

Tragedy struck the Lincoln family when Abraham was just nine years old. His mother, Nancy Hanks Lincoln, died from milk sickness, a common ailment in the region. This loss had a profound impact on Lincoln, leaving him with a sense of abandonment and loss that would linger throughout his life.

After his mother’s death, Lincoln’s father remarried to Sarah Bush Johnston, a widow with three children of her own. Sarah played a crucial role in Lincoln’s life, providing stability and encouragement. Despite the family’s limited resources, she recognized Abraham’s intellectual potential and encouraged his love for learning.

Lincoln’s formal education was minimal, consisting of sporadic attendance at frontier schools where he learned basic reading, writing, and arithmetic. However, his education extended far beyond the classroom. With limited access to books, Lincoln became an avid reader, often walking long distances to borrow volumes from neighbors. His self-directed study included the Bible, Aesop’s Fables, Shakespeare’s works, and other classics.

The challenges of frontier life compelled Lincoln to work from a young age. He took on various jobs, including farm labor, rail-splitting, and working as a store clerk and postmaster. These experiences not only instilled a strong work ethic but also exposed him to the realities of life on the expanding American frontier.

In 1830, seeking better economic prospects, the Lincoln family moved to Illinois. Abraham Lincoln, now in his twenties, began to strike out on his own. His years in Illinois were marked by various jobs and continued struggles. He served in the Illinois militia during the Black Hawk War of 1832, gaining some exposure to military life.

Lincoln’s entry into the world of politics provided both opportunities and challenges. He began his political career in the Illinois State Legislature as a member of the Whig Party, serving multiple terms during the 1830s. However, political success did not shield him from personal setbacks. In 1832, he experienced his first electoral defeat when he ran for the Illinois State Legislature and lost.

Despite this setback, Lincoln persisted in his political pursuits and continued to study law on his own. He gained admission to the Illinois bar in 1836 and commenced his legal practice in Springfield. His legal career flourished, and he earned a reputation for honesty, fairness, and a keen intellect.

In 1842, Lincoln married Mary Todd, a woman from a prominent Kentucky family. The couple faced personal tragedies, including the death of their second son, Edward, at a young age. Lincoln’s responsibilities as a husband and father added to the complexities of his life, and his marriage experienced its share of challenges.

As the nation grappled with the divisive issue of slavery in the 1850s, Lincoln found himself at the center of the political maelstrom. The passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854 and the subsequent events, including the violent clashes in Kansas and the infamous Dred Scott decision by the Supreme Court, intensified the national debate.

In 1858, Lincoln engaged in a series of debates with Senator Stephen A. Douglas during the Illinois Senate race. Though he lost the election, these debates elevated Lincoln’s national profile and solidified his reputation as a skilled orator and a staunch opponent of the spread of slavery.

The personal struggles of Lincoln’s life converged with the seismic challenges facing the nation. The issue of slavery had reached a boiling point, and the election of 1860 saw Lincoln become the first Republican president. Southern states, fearing the impact of Lincoln’s anti-slavery stance, began to secede from the Union, setting the stage for the Civil War.

Lincoln’s presidency was marked by the monumental struggle to preserve the Union. As the nation descended into war, he faced unprecedented challenges, both on the battlefield and on the home front. The staggering loss of life and the complexities of military strategy weighed heavily on him.

The personal toll of the war was evident in Lincoln’s appearance. He aged rapidly, and the burden of leadership manifested physically. The weight of the nation’s divisions, coupled with the loss of countless lives, including his own son Willie, contributed to a heavy personal toll.

The Emancipation Proclamation, issued in 1863, represented a personal and moral struggle for Lincoln. While he had always opposed the expansion of slavery, the proclamation signaled a transformative shift, aligning the Union’s cause with the abolition of slavery. This decision reflected both a moral conviction and a strategic calculation about the future of the nation.

Lincoln’s personal struggles were perhaps most evident in his interactions with the public and the soldiers on the front lines. He took the time to visit wounded soldiers and comfort grieving families, displaying a deep empathy that resonated with the American people. His famous letter to Mrs. Lydia Bixby, a mother who had lost five sons in the war, exemplifies his ability to connect on a deeply personal level.

The weight of the war’s toll on the nation, combined with the personal challenges of Lincoln’s life, culminated in his famous Gettysburg Address. Given at the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery on the site of the pivotal Battle of Gettysburg, the address captured the essence of the nation’s struggle and articulated a vision for a “new birth of freedom.”

Tragically, Lincoln’s life was cut short by an assassin’s bullet on April 14, 1865, just days after the end of the war. His assassination marked the culmination of personal and national struggles, leaving a legacy that would endure through the ages.

Abraham Lincoln’s life was a testament to the human capacity for resilience and growth in the face of adversity. From the log cabin in Kentucky to the hallowed halls of the White House, his journey reflected the struggles and triumphs of a nation at a critical juncture. The personal challenges he faced informed his leadership style, fostering empathy, humility, and an unwavering commitment to the principles that define the American experiment in democracy.

Personal Life and Relationships

Abraham Lincoln’s personal life and relationships were marked by triumphs and tragedies, shaping the man who would become the 16th President of the United States. From his early family life in a log cabin to his complex relationships with his wife and children, Lincoln’s personal journey reflects the joys and sorrows that accompany a life dedicated to public service.

Lincoln’s childhood was humble, born to Thomas and Nancy Hanks Lincoln in a log cabin in Hardin County, Kentucky, on February 12, 1809. Tragedy struck early when Lincoln’s mother died when he was just nine years old. The loss of his mother had a profound impact on Lincoln, leaving him with a deep sense of loss and abandonment.

Following his mother’s death, Lincoln’s father, Thomas, remarried to Sarah Bush Johnston, a widow with three children of her own. Sarah played a pivotal role in Lincoln’s life, providing emotional support and stability during his formative years. Despite the family’s limited resources, she recognized Lincoln’s intellectual potential and encouraged his love for learning.

In 1830, seeking better economic opportunities, the Lincoln family moved to Illinois, where Abraham Lincoln, now in his twenties, began to establish himself. This period marked the beginning of Lincoln’s independent life, as he took on various jobs and started to engage in local politics.

Lincoln’s personal life took a significant turn in 1839 when he met Mary Todd, a vivacious and well-educated young woman from a prominent Kentucky family. The two were engaged in 1840 but faced a series of personal and financial challenges that led to a temporary breakup. However, they eventually reconciled and were married on November 4, 1842.

The marriage between Abraham Lincoln and Mary Todd was a union of contrasts. Mary came from a well-connected and affluent family, while Lincoln’s background was one of poverty and hardship. Despite their differences, they shared a deep emotional connection and a mutual respect for each other.

The Lincolns went on to have four sons: Robert, Edward, William, and Thomas. However, their family life was marked by personal tragedies. Edward, their second son, died at the young age of four in 1850. This loss deeply affected both parents, and Lincoln reportedly grieved intensely over the death of his son.

As Lincoln’s political career progressed, his relationship with Mary faced its share of challenges. Mary Todd Lincoln, while intelligent and politically astute, struggled with mental health issues and faced public criticism. The stresses of Lincoln’s political life, combined with the burdens of the nation during the Civil War, took a toll on their relationship.

Despite the strains on their marriage, the Lincolns shared a genuine bond. Mary played a supportive role during Lincoln’s political career, providing advice and engaging in political discussions. Her social skills and connections were valuable assets, particularly during Lincoln’s presidency.

The White House, during Lincoln’s tenure, became a reflection of both his leadership and his family life. The Lincolns faced the immense personal and emotional toll of the Civil War, with Mary experiencing the loss of friends and family members who fought on both sides of the conflict. The death of their son Willie in 1862 added to the weight of their personal struggles.

Abraham Lincoln’s parenting style was characterized by a balance of discipline and affection. He was known for being indulgent with his sons, allowing them to explore the White House freely. His interactions with his children were marked by warmth and a genuine interest in their well-being.

While the presidency brought unparalleled challenges, Lincoln’s role as a father remained important to him. He took time to engage with his children, whether through reading to them or participating in games. His relationship with his youngest son, Tad, was particularly close, and Tad often accompanied his father to official events and meetings.

The personal challenges faced by the Lincoln family extended to the nation as a whole. The Civil War brought unprecedented loss and suffering, and Lincoln, burdened by the weight of the conflict, sought solace in his family. The strains on his marriage and the grief over the loss of loved ones mirrored the collective pain experienced by the nation.

Lincoln’s personal struggles were evident in his appearance as well. The burdens of leadership, combined with the grief of the war, aged him rapidly. His haggard appearance and the lines on his face spoke to the personal toll of the presidency and the immense challenges faced by the nation.

As the war neared its conclusion in 1865, the Lincolns faced the prospect of reconstruction and healing. Lincoln’s second inaugural address, delivered on March 4, 1865, reflected his vision for a reunified nation. He called for “malice toward none” and “charity for all,” emphasizing the need for reconciliation and unity.

Tragically, Abraham Lincoln’s life was cut short by an assassin’s bullet on April 14, 1865, just days after the war’s conclusion. His assassination marked a somber end to a presidency marked by personal and national struggles. The mourning that swept the nation mirrored the personal grief experienced by the Lincoln family.

The legacy of Abraham Lincoln’s personal life and relationships endures through the ages. His marriage to Mary Todd, marked by challenges and love, reflects the complexities of personal relationships amid the tumult of political life. The losses suffered by the Lincoln family mirrored the collective pain of the nation during the Civil War.

Lincoln’s ability to navigate personal and familial struggles while leading a nation through its darkest hour is a testament to his resilience and character. His commitment to principles of unity and equality, as articulated in the Gettysburg Address and the Emancipation Proclamation, was not only a reflection of his political philosophy but also an expression of his deeply held beliefs about the nature of the American experiment.

In the end, Abraham Lincoln’s personal life and relationships were woven into the fabric of his presidency and the nation’s history. His journey from a log cabin in Kentucky to the White House, marked by personal triumphs and tragedies, remains a poignant and enduring chapter in the story of America.

Views on Slavery

Abraham Lincoln’s views on slavery evolved throughout his life, reflecting the complex and shifting dynamics of the institution in American society. From his early encounters with slavery on the frontier to his leadership during the Civil War, Lincoln’s stance on slavery transformed from one of pragmatic opposition to a steadfast commitment to its abolition, culminating in the Emancipation Proclamation and his pursuit of the 13th Amendment.

Lincoln’s early exposure to slavery occurred during his childhood in Kentucky and Indiana. Growing up on the frontier, he witnessed the presence of slavery, as some families in the region owned enslaved individuals. However, his family did not own slaves, and their economic circumstances were such that they were often struggling to make ends meet.

The death of Lincoln’s mother, Nancy Hanks Lincoln, when he was just nine years old, added a layer of complexity to his early experiences with slavery. After his mother’s death, his father, Thomas Lincoln, remarried to Sarah Bush Johnston, a widow with three children. The Lincolns’ blended family did not own slaves, but their economic challenges persisted.

As Lincoln ventured into the realm of politics and law, his views on slavery became more pronounced. In the Illinois State Legislature during the 1830s, Lincoln aligned himself with the Whig Party, which generally opposed the expansion of slavery into new territories. However, his early political career did not center explicitly on the issue of slavery; rather, it focused on economic development, infrastructure, and issues relevant to the growing state of Illinois.

Lincoln’s personal and political views on slavery began to crystallize during his time in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1847 to 1849. While he was a member of the Whig Party during his single term, the issue of the Mexican-American War brought the question of slavery to the forefront. Lincoln initially supported the war, but he grew increasingly critical and called for President James K. Polk to specify the exact spot where hostilities began. This scrutiny marked a shift in his political stance, foreshadowing a more principled approach to issues related to slavery.

Upon leaving Congress, Lincoln returned to Springfield, Illinois, and resumed his legal practice. During the 1850s, the national debate over the expansion of slavery intensified, fueled by events such as the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854. This act, championed by Senator Stephen A. Douglas, allowed territories to decide the issue of slavery through popular sovereignty, effectively repealing the Missouri Compromise of 1820.

The turmoil surrounding the Kansas-Nebraska Act rekindled Lincoln’s political ambitions. By this time, the Whig Party was disintegrating, and Lincoln found a new political home within the newly formed Republican Party, an anti-slavery coalition. He recognized the moral and political implications of the slavery debate, and his commitment to preventing its spread gained prominence.

The Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858 marked a turning point in Lincoln’s political career and showcased his evolving views on slavery. As the Republican candidate for the U.S. Senate, Lincoln engaged in a series of debates with Senator Stephen A. Douglas, who advocated for popular sovereignty on the issue of slavery. Lincoln articulated a more principled stance, arguing that the nation could not endure permanently half slave and half free.

In his famous House Divided speech delivered in Springfield in 1858, Lincoln stated, “A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free.” This declaration captured the essence of his evolving perspective on slavery. While he did not advocate for immediate abolition, he firmly opposed the extension of slavery into new territories.

The 1858 Senate race, which Lincoln ultimately lost to Douglas, elevated Lincoln’s national profile. His articulation of a moral opposition to the expansion of slavery resonated with anti-slavery sentiments in the North. While he did not win the Senate seat, the debates set the stage for his future political ambitions and solidified his position as a prominent figure within the Republican Party.

The 1860 presidential election marked a critical juncture in Lincoln’s views on slavery. As the Republican nominee, he ran on a platform opposing the extension of slavery into new territories. The election’s outcome triggered the secession crisis, as Southern states feared the impact of Lincoln’s anti-slavery policies on their institution.

When Lincoln assumed the presidency on March 4, 1861, seven Southern states had already seceded from the Union. His primary goal was to preserve the Union, but the issue of slavery remained at the forefront. In his inaugural address, Lincoln reassured the Southern states that he had no intention of interfering with slavery where it already existed but firmly asserted that secession was illegal.

The outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861 transformed the nature of the conflict and Lincoln’s approach to slavery. The initial focus remained on preserving the Union, but as the war unfolded, it became evident that the institution of slavery was central to the Southern economy and war effort.

The turning point came with the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. The proclamation declared all slaves in Confederate-held territory to be free, fundamentally changing the character and purpose of the war. While it did not immediately free all slaves, it shifted the moral tone of the conflict and aligned the Union cause with the broader goal of ending slavery.

Lincoln’s decision to issue the Emancipation Proclamation reflected both moral conviction and strategic calculation. Morally, he had come to view slavery as incompatible with the principles of liberty and equality upon which the nation was founded. Strategically, he recognized the potential to weaken the Confederacy by undermining its economic foundation and gaining support from abolitionist factions in Europe.

The proclamation marked a profound evolution in Lincoln’s views on slavery, transforming him from a pragmatist who opposed its expansion to a leader committed to its abolition. As the war progressed, Lincoln became increasingly convinced that the nation could not endure with slavery persisting in any form.

In 1864, as the war continued and Lincoln faced a contentious reelection campaign, he pushed for the passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution. This amendment, which would officially abolish slavery, represented a definitive break from the past. Lincoln saw the need for a permanent legal measure to eradicate slavery and believed that the amendment would be a fitting conclusion to the war.

The 13th Amendment was ratified on December 6, 1865, several months after Lincoln’s assassination. While Lincoln did not live to see its final ratification, his advocacy for the amendment reflected the culmination of his evolving views on slavery. The nation that emerged from the Civil War was fundamentally altered, with the abolition of slavery enshrined in its constitutional framework.

Abraham Lincoln’s journey from a young man on the frontier witnessing the complexities of slavery to the President who issued the Emancipation Proclamation and advocated for the 13th Amendment reflects a profound evolution in his views. His commitment to preserving the Union shifted from a pragmatic concern for the nation’s stability to a principled stance against the institution of slavery. The trajectory of Lincoln’s views on slavery mirrored the tumultuous times in which he lived, reflecting the broader transformation of the nation during a period of unprecedented crisis.

While Lincoln’s evolution on the issue of slavery has been analyzed and debated by historians, it underscores the complex interplay of moral, political, and strategic considerations that shape leaders and their decisions. Lincoln’s ability to adapt and grow in response to the challenges of his time is a testament to his leadership, pragmatism, and commitment to the enduring principles of freedom and equality.

In the annals of American history, Abraham Lincoln stands as a symbol of leadership during a pivotal moment. His views on slavery, as reflected in his speeches, debates, and ultimately in the policies of his presidency, played a crucial role in shaping the nation’s trajectory. From the plains of the Midwest to the hallowed halls of the White House, Lincoln’s journey encapsulates the moral and political struggle to reconcile the principles of liberty with the institution of slavery.

As we reflect on Lincoln’s legacy, it prompts us to consider the broader implications of leadership in times of crisis. Lincoln’s willingness to confront and reassess his views, particularly on an issue as divisive as slavery, serves as a compelling example for leaders navigating complex and contentious challenges. His legacy challenges us to strive for a more just and inclusive society, guided by the enduring principles that define the American experiment in democracy.

Assassination and Legacy

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln on the evening of April 14, 1865, just days after the end of the Civil War, marked a tragic and fateful conclusion to a presidency that had guided the nation through its darkest hour. Lincoln’s legacy, forged in the crucible of war and shaped by his steadfast commitment to the principles of freedom and equality, endures as a beacon in American history.

On the night of April 14, 1865, President Lincoln attended a play at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. Unbeknownst to him, this seemingly ordinary evening would become one of the most pivotal moments in American history. John Wilkes Booth, a Confederate sympathizer and actor, entered the President’s theater box and shot Lincoln in the back of the head.

The nation awoke to the shocking news of Lincoln’s assassination on the morning of April 15, 1865. The joy that had accompanied the recent end of the Civil War was instantly replaced by grief and sorrow. The President’s death sent shockwaves through the nation, leaving a profound void at a critical juncture of reconstruction and healing.

Lincoln succumbed to his injuries the following day, on April 15, 1865. His death marked the first assassination of a sitting U.S. President and plunged the nation into mourning. The loss of Lincoln, who had steered the nation through its most perilous period, left a profound impact on the collective consciousness of the American people.

The assassination of Lincoln was not an isolated act; it was part of a broader conspiracy that aimed to decapitate the Union government. Booth, along with several co-conspirators, sought to assassinate not only the President but also Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William H. Seward. While the attempts on Johnson and Seward were unsuccessful, Lincoln’s death left an indelible mark on the nation’s history.

Booth’s motives for assassinating Lincoln were rooted in his fervent support for the Confederacy and his belief in white supremacy. As the Union forces secured victory, Booth saw the President’s vision for reconstruction, which included civil rights for freed slaves, as a threat to the Southern way of life. In Booth’s distorted view, assassinating Lincoln was a desperate attempt to preserve the Confederacy’s ideals.

The aftermath of Lincoln’s assassination saw a swift and intense manhunt for Booth and his co-conspirators. On April 26, 1865, Booth was located in a barn in Virginia. Refusing to surrender, he was shot and killed by Union soldiers. The remaining conspirators faced trial, with several receiving harsh sentences, including four who were executed by hanging.

The nation grappled with the loss of Lincoln, mourning a leader who had become a symbol of hope, unity, and moral purpose. As the first U.S. President to be assassinated, Lincoln’s death left an indelible imprint on the American psyche. His funeral procession, which spanned multiple cities and states, became a solemn journey of mourning and reflection.

Lincoln’s legacy, however, extended far beyond the immediate aftermath of his assassination. His leadership during the Civil War and his unwavering commitment to the principles of freedom and equality left an enduring impact on the nation. As the country entered the challenging era of reconstruction, Lincoln’s vision for a united and reconciled nation continued to guide policymakers.

The Gettysburg Address, delivered by Lincoln on November 19, 1863, during the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery at the site of the Battle of Gettysburg, remains one of the most iconic speeches in American history. In just over two minutes, Lincoln articulated a vision for a nation “conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” This concise and powerful statement encapsulates the essence of American democracy and became a touchstone for the nation’s identity.

Another pivotal aspect of Lincoln’s legacy was the Emancipation Proclamation, issued on January 1, 1863. While it did not immediately free all slaves, it transformed the character and purpose of the Civil War by aligning the Union cause with the abolition of slavery. The proclamation laid the groundwork for the eventual passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which officially abolished slavery in the United States.

Lincoln’s commitment to preserving the Union while simultaneously addressing the moral issue of slavery demonstrated a nuanced and visionary approach to leadership. His ability to navigate the complexities of a nation torn apart by war and ideological divisions showcased his pragmatism, empathy, and unwavering dedication to the principles of democracy.

In the years following Lincoln’s death, the process of reconstruction unfolded. His vision for a reconciled nation faced significant challenges as policymakers grappled with the complexities of integrating the Southern states back into the Union and establishing civil rights for newly emancipated slaves. Despite the difficulties, Lincoln’s legacy continued to guide those who sought to build a more just and inclusive society.

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln left an enduring impact on the American presidency and the nation’s history. The subsequent presidents faced the daunting task of navigating the complexities of reconstruction and healing a fractured nation. Lincoln’s absence loomed large, and his successors grappled with the formidable challenges of implementing his vision in a post-war America.

Over time, Lincoln’s image evolved into that of a revered figure, an American hero whose leadership transcended the turbulent times in which he lived. His humble origins, marked by poverty and frontier hardship, endeared him to the American people as a symbol of the possibility of upward mobility and success through hard work and perseverance.

The mourning and reverence for Lincoln continued to shape the nation’s collective memory. Memorials, monuments, and institutions dedicated to his legacy proliferated across the country. The Lincoln Memorial, situated on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., became a symbol of national unity and a place of reflection for millions of visitors.

The legacy of Abraham Lincoln extended beyond the United States. His commitment to the principles of freedom and equality resonated on the global stage, influencing leaders and movements around the world. The enduring appeal of Lincoln’s vision for a nation dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal transcended time and borders.

In the realm of literature and popular culture, Abraham Lincoln became an iconic figure. Countless books, films, and artistic representations explored his life, leadership, and the enduring impact of his presidency. The Lincoln mythos became a powerful narrative thread woven into the fabric of American identity.

Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, while a tragic and abrupt end to his life, did not diminish his legacy. Instead, it elevated him to the status of a martyr for the cause of democracy and equality. The nation’s collective memory of Lincoln focused on his role as the Great Emancipator, the leader who guided the United States through its greatest trial and paved the way for a more inclusive and just society.

As the United States continued to grapple with issues of civil rights and equality in the decades that followed, Lincoln’s legacy remained a touchstone. The struggles for civil rights in the 20th century found inspiration in the principles articulated by Lincoln during the Civil War. His vision for a nation committed to the proposition that all people are entitled to the same fundamental rights and opportunities reverberated through the ongoing quest for justice.

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln left an indelible mark on the nation, forever intertwining his legacy with the tumultuous period of the Civil War and reconstruction. Lincoln’s enduring impact lies not only in the policies he championed but also in the ideals and

principles that continue to shape the American experiment. The legacy of Abraham Lincoln serves as a beacon, reminding the nation of the enduring struggle for freedom, equality, and unity.

The enduring resonance of Lincoln’s legacy is evident in the continued study and reverence afforded to his life and presidency. Historians, scholars, and educators delve into the complexities of his leadership, examining the nuanced decisions he made and the profound impact they had on the trajectory of the nation. The lessons drawn from Lincoln’s presidency extend beyond the pages of history books, providing insights into the challenges of leadership during times of crisis.

One aspect of Lincoln’s legacy that stands out is his ability to bridge the gap between competing ideals and forge a common national identity. He confronted the profound contradiction of a nation conceived in liberty yet entangled in the institution of slavery. Lincoln’s unwavering commitment to preserving the Union while addressing the moral stain of slavery demonstrated a pragmatic and visionary approach to leadership.

The principles articulated by Lincoln during his presidency, encapsulated in iconic speeches like the Gettysburg Address, transcended the specific context of the Civil War. They became foundational elements of the American creed, guiding subsequent generations in their pursuit of a more perfect union. The notion that a nation, dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal, must strive for unity, justice, and freedom resonates through the annals of American history.

The challenges faced by the nation in the aftermath of the Civil War, as it sought to heal its wounds and redefine its identity, mirrored the personal struggles of individuals and communities. The legacy of Lincoln provided a moral compass during Reconstruction, encouraging a path toward reconciliation and a commitment to civil rights. While the journey toward justice was fraught with setbacks, Lincoln’s vision continued to inspire those who sought to build a more inclusive and egalitarian society.

The evolution of Abraham Lincoln from a self-educated prairie lawyer to the revered leader of a divided nation underscores the transformative power of leadership. His ability to navigate the complexities of his time, adapt to changing circumstances, and remain steadfast in his commitment to core principles serves as a model for leaders across various domains.

In the realm of civil rights, Lincoln’s legacy intersected with the ongoing struggles for equality in the 20th century. The Civil Rights Movement drew inspiration from the principles espoused by Lincoln, particularly the idea that the nation should aspire to live up to its foundational commitment to equality. Figures like Martin Luther King Jr. invoked Lincoln’s words and vision in their quest for justice and civil rights, recognizing the enduring relevance of his moral compass.

The Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., dedicated in 1922, became a symbolic space for gatherings and reflections on civil rights. It was at the steps of the Lincoln Memorial that Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. The juxtaposition of Lincoln’s legacy with the contemporary struggle for civil rights underscored the enduring impact of his vision on the quest for racial equality.

In literature and popular culture, Abraham Lincoln continued to capture the imagination of artists, writers, and filmmakers. His life and presidency became the subject of countless works, each contributing to the rich tapestry of Lincoln’s legacy. The nuanced exploration of his character, the challenges he faced, and the moral dilemmas he confronted added depth to the understanding of his leadership.

While the assassination of Abraham Lincoln remains a somber chapter in American history, it did not overshadow the enduring impact of his presidency. The tragedy of his death served to elevate his status to that of a national martyr, reinforcing the resonance of his legacy. The collective mourning that followed his assassination reflected not only the grief over the loss of a leader but also a recognition of the profound contributions he made to the nation.

The legacy of Abraham Lincoln extends beyond the borders of the United States, influencing global perceptions of democracy, leadership, and the pursuit of human rights. His journey from a log cabin on the American frontier to the presidency became a symbol of the transformative potential embedded in the democratic experiment. Leaders and movements around the world found inspiration in Lincoln’s commitment to liberty and equality, recognizing the enduring relevance of his principles.