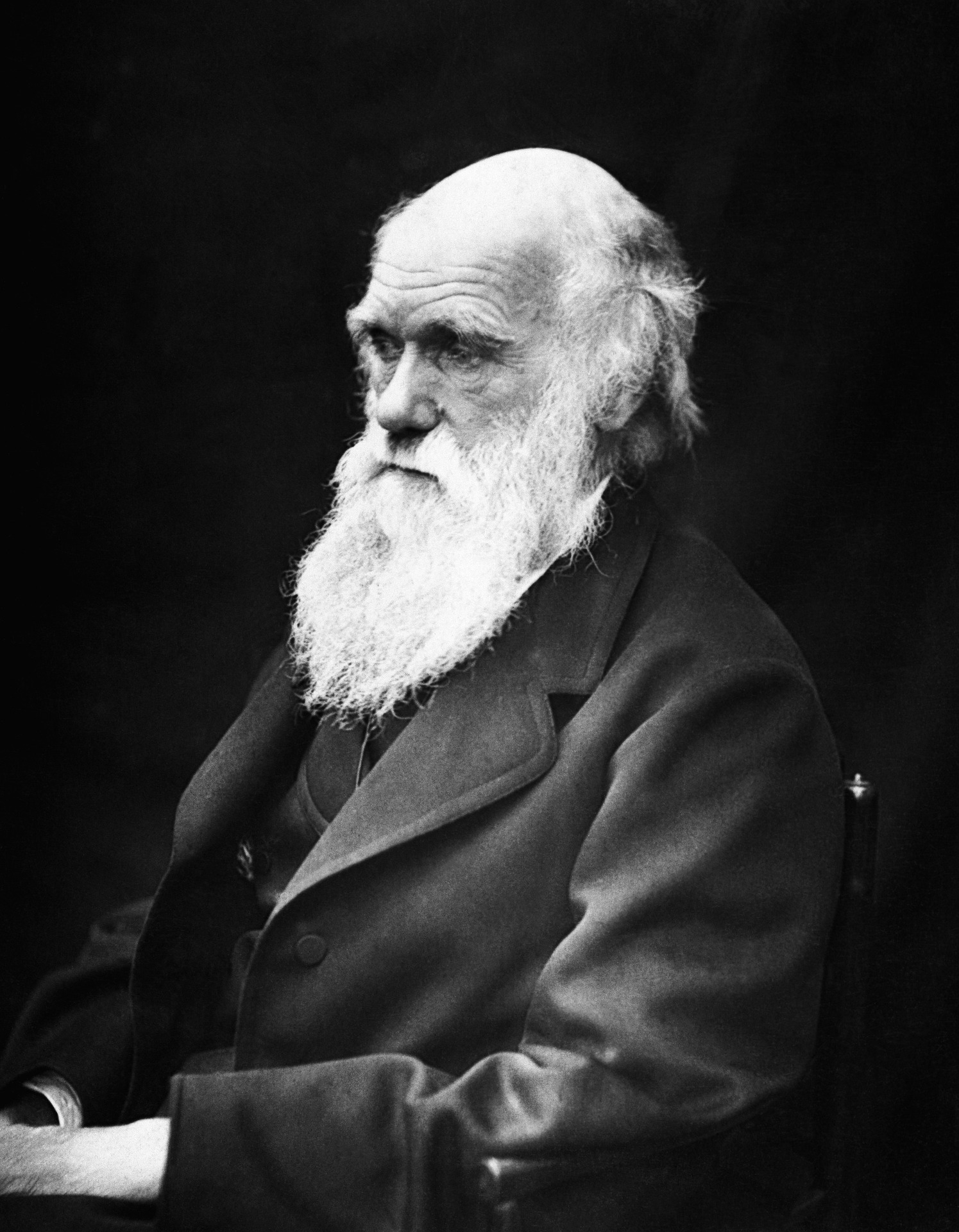

Charles Darwin (1809-1882) was an English naturalist and biologist. He is best known for his theory of evolution by natural selection, outlined in his seminal work “On the Origin of Species,” published in 1859. Darwin’s groundbreaking ideas revolutionized the understanding of the origin and diversification of species, shaping the field of biology.

Early Life and Education

Charles Darwin, born on February 12, 1809, in Shrewsbury, England, into a prominent and intellectually inclined family, was the fifth of six children. His father, Robert Darwin, was a wealthy doctor and financier, while his mother, Susannah Darwin, died when Charles was only eight years old. This early loss had a profound impact on him.

Young Darwin exhibited an early interest in nature and collecting specimens, a passion that was encouraged by his father. Robert Darwin recognized his son’s potential and sent him to Shrewsbury School, where Charles’s fascination with the natural world continued to flourish. However, academic studies did not captivate him as much as his self-directed explorations of the outdoors.

In 1825, at the age of 16, Darwin enrolled at the University of Edinburgh with the intention of studying medicine. Yet, he found the medical curriculum uninspiring, and his interest waned. Instead, he became engrossed in natural history, attending lectures by prominent naturalists and joining the Plinian Society, a student group dedicated to the study of natural phenomena.

Darwin’s father, concerned about his son’s academic focus, decided to redirect him toward a more conventional career path. In 1828, Charles transferred to the University of Cambridge to study theology with the expectation that he would become a clergyman. However, his passion for natural history persisted.

At Cambridge, Darwin befriended John Stevens Henslow, a botanist and mentor who played a crucial role in shaping Darwin’s future. Henslow’s influence extended beyond the classroom, as he recommended Darwin for the position of naturalist on the HMS Beagle—a ship about to embark on a surveying expedition around the world.

Darwin’s journey on the Beagle, which lasted from 1831 to 1836, proved to be a transformative period in his life. The expedition took him to various continents, including South America, Australia, and Africa, providing him with unparalleled opportunities to observe and collect specimens from diverse environments. His encounters with the unique flora and fauna of these regions laid the groundwork for his later theories on evolution.

During the voyage, Darwin meticulously documented his observations, collecting specimens and keeping detailed notes on geology, zoology, and anthropology. His exposure to different ecosystems, geological formations, and fossils sparked his curiosity and planted the seeds of ideas that would later blossom into groundbreaking theories.

One of the most influential stops on the Beagle’s journey was the Galápagos Islands, where Darwin observed variations among species from island to island. This experience, coupled with his broader observations, led him to question the prevailing view of species as unchanging creations. The concept of evolution started to take root in Darwin’s mind.

Upon returning to England in 1836, Darwin faced the monumental task of organizing and analyzing the wealth of data he had collected. Over the next several years, he delved into his studies, corresponded with fellow naturalists, and began formulating his groundbreaking ideas about the transmutation of species.

In 1839, Darwin married his cousin, Emma Wedgwood, and the couple eventually had ten children. Despite his family responsibilities, Darwin continued his scientific endeavors, publishing works on topics ranging from barnacles to the expression of emotions in animals and humans.

In 1859, Darwin published his most influential work, “On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection.” This seminal book presented his theory of natural selection, a mechanism through which species gradually evolve over time. Darwin argued that individuals with advantageous traits are more likely to survive and reproduce, passing on these traits to subsequent generations—a process he termed “natural selection.”

The publication of “On the Origin of Species” ignited intense debates within the scientific community and society at large. The idea of evolution challenged prevailing religious and scientific beliefs about the fixed nature of species. While some embraced Darwin’s theory, others vehemently opposed it.

Darwin’s meticulous research, extensive travels, and revolutionary ideas laid the foundation for modern evolutionary biology. His work not only reshaped our understanding of the natural world but also had profound implications for fields as diverse as anthropology, paleontology, and genetics.

Voyage on HMS Beagle

The voyage of HMS Beagle, spanning from 1831 to 1836, stands as a seminal chapter in the life of Charles Darwin and played a pivotal role in shaping his revolutionary theory of evolution through natural selection. The expedition, primarily a hydrographic survey of South America, became a transformative journey of scientific exploration, during which Darwin’s observations and experiences laid the groundwork for one of the most significant scientific theories in history.

The HMS Beagle set sail on December 27, 1831, with the primary mission of conducting coastal surveys of South America and the surrounding regions. Under the command of Captain Robert FitzRoy, the ship’s complement included a young naturalist, Charles Darwin, who had been recommended for the position by his mentor, Professor John Stevens Henslow of Cambridge University.

The voyage took the Beagle to various destinations, including South America, the Galápagos Islands, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. Darwin’s role as the ship’s naturalist was to collect specimens and make detailed observations of the geology, flora, fauna, and indigenous cultures encountered during the journey.

One of the key stops on the voyage was South America, where Darwin spent a considerable amount of time exploring the continent’s diverse landscapes. In Brazil, he marveled at the rich biodiversity of the rainforests and made extensive collections of plants, insects, and fossils. His observations of the stratigraphy of the Andes Mountains provided crucial insights into the geological history of the region.

However, it was the Galápagos Islands that would become synonymous with Darwin’s name and his revolutionary ideas. Arriving at the Galápagos in September 1835, Darwin noted the distinctiveness of the fauna on different islands. Most famously, he observed variations in the beaks of finches from island to island, a discovery that would later play a central role in the development of his theory of natural selection.

The finches’ beak variations suggested adaptation to different ecological niches and environmental conditions, leading Darwin to ponder the role of natural selection in shaping the characteristics of species over time. These insights laid the foundation for his revolutionary theory of evolution, challenging the prevailing view of fixed and unchanging species.

Australia and New Zealand also provided Darwin with valuable opportunities for scientific exploration. In Australia, he encountered unique marsupials, further fueling his curiosity about the distribution of species across different continents. In New Zealand, he witnessed the effects of geological forces on the landscape and collected specimens that contributed to his understanding of the natural world.

The voyage was not without its challenges. The Beagle faced treacherous weather, and the crew encountered various hardships during the long journey. Darwin, prone to seasickness, endured the physical discomforts of the sea while dedicating himself to his scientific pursuits. Despite the difficulties, the voyage provided Darwin with the time and opportunity to develop his scientific skills and observations.

As the Beagle continued its journey, it made a significant stop in the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa, where Darwin explored the local geology and observed the diverse flora and fauna of the region. His encounters with different climates, ecosystems, and geological formations contributed to a growing body of evidence that challenged the prevailing views of the fixity of species.

The HMS Beagle returned to England on October 2, 1836, completing its circumnavigation of the globe. Darwin, now laden with a vast collection of specimens, notebooks, and sketches, began the arduous task of analyzing and synthesizing the wealth of information he had gathered during the expedition.

The impact of the voyage on Darwin’s thinking was profound. The meticulous observations and collections made during the journey provided him with a wealth of empirical evidence that contradicted the prevailing views of the time. The geographical distribution of species, the fossil record, and the variations observed in different environments all pointed towards a dynamic and evolving natural world.

Darwin’s experiences on the HMS Beagle laid the groundwork for his groundbreaking theory of evolution. The diversity of life he encountered, coupled with his observations of adaptation and natural variation, challenged the prevailing paradigm of fixed and unchanging species. The voyage marked a turning point in scientific history, setting the stage for the publication of “On the Origin of Species” in 1859 and forever altering our understanding of the natural world.

Evolution by Natural Selection

Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection, outlined in his seminal work “On the Origin of Species,” represents one of the most revolutionary ideas in the history of science. This groundbreaking theory fundamentally transformed our understanding of the diversity of life on Earth and how species adapt and change over time.

Darwin’s theory, first presented in 1859, was the culmination of years of observation, experimentation, and analysis. The key concept at the heart of evolution by natural selection is the idea that species evolve over time through a process of differential survival and reproduction. The mechanism driving this process is natural selection, a concept that Darwin meticulously developed based on various observations and evidence.

At its core, natural selection is a straightforward and elegant idea. It begins with the recognition that within any population, there is natural variation among individuals. These variations can be attributed to genetic differences, and they influence traits such as size, color, or behavior. Importantly, some of these variations provide individuals with a better chance of surviving and reproducing in their specific environment.

In every generation, more individuals are born than can possibly survive and reproduce. This leads to what Darwin termed a “struggle for existence” as individuals compete for limited resources. In this competitive environment, individuals with advantageous traits—traits that enhance their ability to survive and reproduce—are more likely to pass on these beneficial traits to their offspring.

The critical aspect of natural selection is that it is not a conscious or directed process. Nature, through the environment and its challenges, serves as the selective agent. Traits that confer a survival advantage lead to greater reproductive success, and over time, these advantageous traits become more prevalent in the population.

Darwin illustrated this concept with the famous example of the finches on the Galápagos Islands. He observed that different species of finches on different islands had distinct beak shapes, each adapted to the specific types of food available on their respective islands. The beaks of the finches had evolved through natural selection, favoring those shapes that provided the most efficient means of obtaining food in each unique environment.

The theory of evolution by natural selection also addresses the fossil record, providing an explanation for the gradual changes observed over geological time. As species evolve, transitional forms may arise, and these intermediary species are expected to leave behind fossils that reflect their intermediate characteristics. Subsequent paleontological discoveries have indeed uncovered such transitional fossils, supporting the predictions of Darwin’s theory.

Moreover, the field of comparative anatomy offers additional evidence for evolution. Similarities in the anatomical structures of different species, particularly those sharing a common evolutionary ancestry, provide insights into the gradual modifications that have occurred over time. Homologous structures, such as the bones in the limbs of vertebrates, point to a common origin despite variations in function.

Darwin’s theory of evolution also finds support in embryology, where similarities in early developmental stages among different species suggest shared ancestry. The presence of vestigial organs, seemingly functionless structures that have lost their original purpose through evolution, further supports the idea of gradual modification over time.

While the concept of evolution by natural selection has withstood the test of time and accumulated substantial supporting evidence, it was initially met with significant controversy. The prevailing scientific and religious views of the mid-19th century were grounded in the idea of fixity of species, a belief that species were individually created and immutable. Darwin’s theory challenged this deeply ingrained perspective, and the implications of evolution, especially in the context of human ancestry, were met with resistance.

Despite the initial pushback, Darwin’s work gained acceptance over the decades as more evidence from various scientific disciplines corroborated the principles of evolution. The synthesis of Darwinian evolution with Mendelian genetics in the early 20th century, known as the modern synthesis, further solidified the foundation of evolutionary biology.

The theory of evolution by natural selection not only explains the diversity of life on Earth but has broader implications for understanding the unity of life. All living organisms, according to this theory, share a common ancestry and are part of an intricate web of evolutionary relationships.

Darwin’s Observations

Charles Darwin’s groundbreaking theory of evolution by natural selection was the result of meticulous observations made over the course of his life, particularly during his renowned voyage on HMS Beagle from 1831 to 1836. These observations, ranging from the Galápagos Islands to South America and beyond, formed the basis of his revolutionary ideas that challenged the prevailing views on the fixity of species.

One of the pivotal aspects of Darwin’s observations was his exploration of the Galápagos Islands. This archipelago, located in the Pacific Ocean, is renowned for its unique biodiversity. During his visit, Darwin noticed subtle variations among species of finches on different islands. This diversity in beak shapes and sizes struck him as peculiar, especially considering that these finches appeared to be similar to mainland South American species.

Darwin’s keen eye for detail led him to recognize that the variations in finch beaks were adaptations to the specific environments and available food sources on each island. This observation became a cornerstone of his later theory, as it highlighted the role of natural selection in shaping traits based on the demands of the environment. The finches’ beaks were not fixed; instead, they had evolved over time in response to the varying ecological niches of each island.

Beyond the Galápagos, Darwin’s voyage took him to various locations in South America, where he made significant geological and paleontological observations. His encounters with fossils, particularly those of extinct mammals like giant ground sloths and armadillos, provided evidence of a dynamic Earth with a history of life that extended far beyond the span of human existence.

Darwin also noted the presence of fossils resembling existing species, suggesting a connection between past and present life forms. This observation supported the idea that species were not individually created but had evolved over time, undergoing modifications to adapt to changing environments.

During his voyage, Darwin meticulously recorded his observations in notebooks, documenting not only the diversity of species but also their geographical distribution. He observed similarities between the fauna of South America and certain regions of Australia, despite their considerable geographical separation. This observation hinted at a pattern of species distribution that could be explained by the movement and adaptation of organisms over time.

Darwin’s observations were not limited to fauna; he also studied the flora of the regions he visited. His interest in the relationships between plants and their pollinators, as well as the adaptations of plants to their environments, provided additional insights into the interconnected web of life. The diversity and complexity of plant life, like the animal life he encountered, contributed to the broader understanding of the natural world as a dynamic and evolving system.

Furthermore, Darwin was intrigued by the role of geological processes in shaping landscapes. His observations of rock formations, the uplift of mountains, and the gradual changes in the Earth’s crust informed his understanding of the forces at play in shaping the planet. These geological insights were integral to his later considerations of the deep time required for the slow process of evolution to unfold.

The depth and breadth of Darwin’s observations extended to the behavioral aspects of organisms. His studies of animal behavior, including the courtship rituals of birds and the parenting behaviors of various species, provided a rich understanding of the complexity of life beyond its physical characteristics. These behavioral observations added a layer of nuance to his later discussions on the factors influencing natural selection.

Upon returning to England, Darwin spent years analyzing and synthesizing the wealth of data he had collected. His observations formed the basis of his theory of evolution, and he began to recognize patterns that pointed toward a more profound interconnectedness of all living organisms.

Controversies and Impact

Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection, while now widely accepted in the scientific community, was met with significant controversies and had profound societal and intellectual impacts during his time and in the subsequent years. The revolutionary nature of Darwin’s ideas challenged entrenched beliefs about the origins and diversity of life, sparking debates that extended far beyond the realm of science.

One of the primary controversies surrounding Darwin’s theory was its conflict with prevailing religious views, particularly those rooted in creationism. The prevailing belief, based on religious doctrines, was that species were individually created by a divine force and remained unchanged over time. Darwin’s proposal that species evolved through a natural, gradual process challenged the biblical narrative of creation and stirred tensions between science and religion.

The publication of “On the Origin of Species” in 1859 intensified these tensions. The idea that humans shared a common ancestry with other species and were not specially created raised profound theological questions. The concept of natural selection, operating without a guiding hand, challenged the notion of a purposeful and directed creation.

Religious figures and institutions reacted strongly to Darwin’s ideas. Some viewed evolution as incompatible with religious teachings, leading to a perceived conflict between science and faith. Clergy and religious authorities raised objections, and the public response varied widely. While some embraced the new scientific paradigm without abandoning their religious beliefs, others staunchly opposed any challenge to traditional interpretations of creation.

The controversy also extended to the scientific community, where individuals with vested interests in existing paradigms were resistant to change. Notable scientists, including prominent naturalists and anatomists, initially opposed Darwin’s theory. Richard Owen, a respected contemporary of Darwin, was critical of natural selection, while others, like Louis Agassiz, maintained their adherence to a more fixed view of species.

However, as the evidence in favor of evolution accumulated over time, the scientific community began to accept Darwin’s ideas. The emerging field of paleontology, the discovery of transitional fossils, and advancements in genetics all provided additional support for the theory. The synthesis of Darwinian evolution with Mendelian genetics in the early 20th century, known as the modern synthesis, solidified the acceptance of natural selection as the driving force of evolution.

Darwin’s theory also faced challenges in the realm of social and ethical implications. The concept of “survival of the fittest,” often associated with Darwinism, was misappropriated to justify social policies that promoted competition and inequality. Social Darwinism, a term coined later, distorted Darwin’s scientific ideas into a misguided application in human society, suggesting that certain races or social classes were inherently superior based on evolutionary principles.

Despite these misinterpretations, Darwin himself was cautious about extending his theories to human societies. In “The Descent of Man,” published in 1871, he explored the evolution of humans but did not propose a strict hierarchy based on racial or social factors. Nevertheless, the misapplication of Darwinian ideas to justify social inequality persisted, contributing to debates on eugenics and other contentious topics.

Darwin’s impact reached beyond scientific and social circles into broader cultural and philosophical realms. His ideas influenced thinkers in various fields, including philosophy, literature, and psychology. The notion of a dynamic and evolving world challenged static and deterministic views, fostering a more fluid understanding of the natural order.

Literary figures such as Thomas Henry Huxley, known as “Darwin’s Bulldog,” actively defended and popularized Darwinian ideas. Huxley’s debates with religious authorities and his advocacy for evolution contributed to the public discourse surrounding the theory. The impact of Darwin’s ideas was also evident in the works of novelists, including George Eliot and H.G. Wells, who incorporated evolutionary themes into their writings.

Darwin’s impact on psychology was notable as well. His exploration of emotions in humans and animals, detailed in “The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals,” laid the groundwork for the study of ethology and comparative psychology. The recognition of shared emotional expressions among species highlighted the continuity of life and supported Darwin’s broader thesis of a common ancestry.

In the realm of philosophy, Darwin’s ideas influenced thinkers such as Herbert Spencer, who coined the phrase “survival of the fittest” and applied it not only to biology but also to social and economic realms. The pervasive influence of Darwinism led to a reevaluation of traditional philosophical concepts, challenging teleological views of nature and human existence.

The controversies surrounding Darwin’s theory gradually subsided as evidence from various disciplines continued to support the principles of evolution. By the 20th century, the scientific community had largely embraced the theory of evolution by natural selection as the foundational framework for understanding the diversity of life on Earth.

Later Life and Legacy

In the latter part of his life, Charles Darwin continued to contribute to science, further refining his ideas and addressing new areas of inquiry. His later life was marked by continued scientific exploration, extensive writing, and the reception of both acclaim and criticism. Darwin’s legacy, however, extended well beyond his lifetime, profoundly influencing biology and shaping the course of scientific inquiry for generations to come.

After the publication of “On the Origin of Species” in 1859, Darwin dedicated himself to further research and writing. He delved into various aspects of biology, publishing works that expanded on his evolutionary theories and explored other scientific questions. One notable example is “The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex,” published in 1871, where Darwin applied evolutionary principles to the understanding of human evolution and discussed sexual selection.

In “The Descent of Man,” Darwin explored the similarities between humans and other animals, emphasizing the shared ancestry and evolutionary continuity. He argued that traits such as emotions, moral instincts, and social behaviors could be understood in an evolutionary context, emphasizing the adaptive advantages conferred by these traits in the course of human evolution.

Another significant work from this period was “The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals” (1872), in which Darwin investigated the universality of emotional expressions. Through detailed observations and comparisons, he argued that many emotional expressions in humans and animals had common evolutionary origins, reinforcing the idea of a shared biological heritage.

Throughout his later years, Darwin also conducted studies in botany, investigating the mechanisms of plant reproduction. His work on plant fertilization, particularly in orchids, was detailed in his book “The Various Contrivances by Which Orchids Are Fertilised by Insects” (1862). This research showcased Darwin’s continued dedication to meticulous observation and experimentation, illustrating his interdisciplinary approach to the natural sciences.

Darwin’s later life was not without challenges. He faced health issues, including bouts of illness that affected his ability to work consistently. Nevertheless, his passion for science remained undiminished. Darwin corresponded with numerous scientists, exchanging ideas and insights that contributed to the broader scientific community.

His wife, Emma Darwin, played a crucial role in supporting his scientific endeavors. Emma, a deeply religious woman, had concerns about the implications of her husband’s work on religion, but she respected his dedication to truth and science. The couple had a loving and supportive relationship, and Emma’s role in nurturing Darwin’s work and managing his health during periods of illness was significant.

In 1881, Charles Darwin’s health deteriorated further. Despite his illness, he continued working on his research until he passed away on April 19, 1882, at the age of 73. His death marked the end of an era but not the end of his influence.

Darwin’s legacy extended far beyond his lifetime, shaping the trajectory of scientific inquiry and transforming the way we understand life on Earth. His theory of evolution by natural selection laid the foundation for modern biology, providing a unifying framework that explains the diversity and interconnectedness of all living organisms.

The impact of Darwin’s ideas reverberated through the scientific community in the years following his death. The modern synthesis of the early 20th century integrated Darwinian evolution with Mendelian genetics, providing a more comprehensive understanding of how traits are inherited and how natural selection operates at the genetic level. This synthesis solidified the acceptance of Darwinian evolution in mainstream biology.

Darwin’s influence extended into the field of paleontology, where subsequent discoveries of transitional fossils further substantiated his theories. Advances in molecular biology and genetics in the 20th century provided additional support for the concept of a common ancestry and the gradual accumulation of genetic changes over time.

In the realm of anthropology, the study of human evolution continued to evolve, drawing on Darwinian principles to explore the origins and development of Homo sapiens. The discovery of ancient hominid fossils and advancements in dating techniques contributed to a more detailed understanding of our evolutionary history.

Beyond the sciences, Darwin’s ideas permeated diverse fields of study. In philosophy, his theories spurred discussions on the nature of existence, morality, and the implications of a naturalistic worldview. The impact of Darwinism was also evident in psychology, where the study of behavior and cognition incorporated evolutionary perspectives.

Darwin’s legacy was not confined to academia; it reached into the broader cultural and societal realms. The acceptance of evolution had implications for education, challenging traditional curricula and prompting debates about the teaching of evolutionary theory in schools. Legal battles, such as the famous Scopes Monkey Trial in 1925, highlighted the tensions between religious beliefs and the teaching of evolution in public education.

The 20th century witnessed the development of the modern environmental movement, drawing inspiration from the interconnected view of nature inherent in Darwin’s work. Conservation biology emerged as a discipline that sought to preserve biodiversity and ecosystems, aligning with the understanding that all living organisms share a common evolutionary history.

As the scientific community celebrated the centennial anniversary of Darwin’s birth in 1909 and the 50th anniversary of the publication of “On the Origin of Species” in 1909, his legacy continued to be honored. The Darwinian revolution had enduring implications, shaping not only the way scientists approached their research but also influencing societal attitudes toward the natural world and humanity’s place within it.